Read the case presentation and join the conversation through the comments in this post!

Case Introduction: An Explosive Mission!

- 56-year-old male patient

- Severe smoker

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia

- Sedentary lifestyle and stress

- A sibling suffered from an acute myocardial infraction

Cardiac markers: Standard angina, intensity of 8-9/10, 3-to-4-h long, and dyspnea (on and off for the past 2 days).

Upon assessment: No angina or equivalent, no pump failure (KK1).

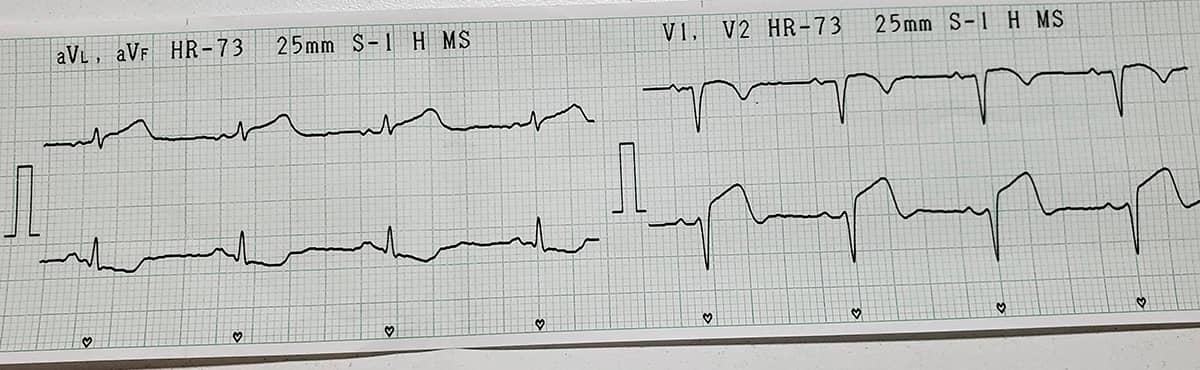

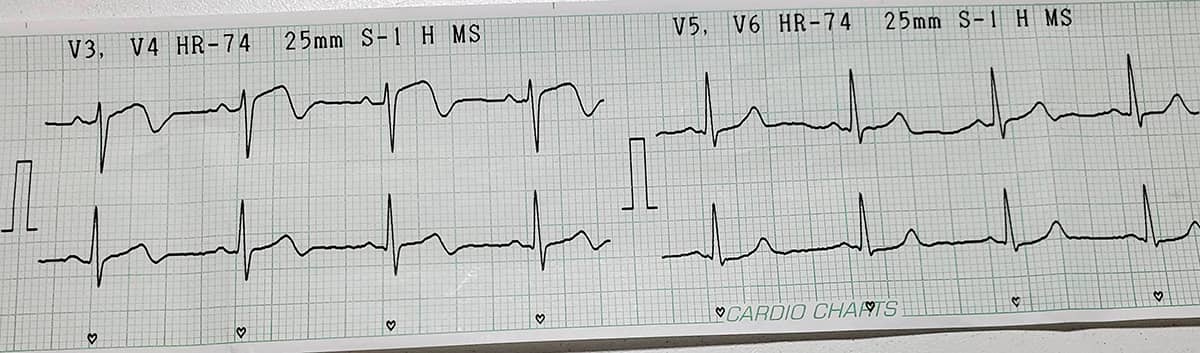

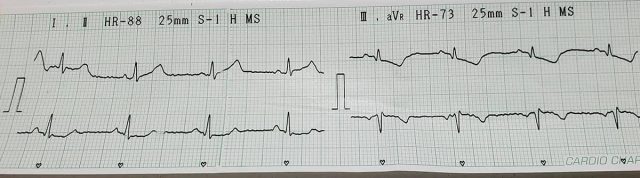

ECG: Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome

Troponin I (high sensitivity): 3795 (cardiac volume over 100)

Coronary angiography: 6F in right radial artery, TIGER 5F diagnostic catheter

- Left main coronary artery: Too short, no significant stenosis.

- Anterior descending artery: Long and medium-sized; severe, 90% stenosis in the middle third and Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 3 flow.

- Circumflex artery: Medium-sized, mild irregularities, no significant stenosis.

- Right coronary artery: Dominant, medium-sized, mild irregularities, no significant stenosis.

PROCEDURE

The balloon’s shaft is inflated and then ruptured proximal to the balloon.

Then, the balloon is extracted with no complications. The control test shows a rupture in the anterior descending artery towards the pericardium, with a mild contrast leak.

Patient still has a burning retroesternal pain and high blood pressure.

A dopamine drip is initiated (400 mg in 250 mL of saline at 10 microdrops/minute), as well as heparin reversal with 2 slowly infused protamine vials.

Se infla el shaft del balón y se rompe proximal al balón.

Posteriormente, se retira el balón sin complicaciones y en test de control se observa ruptura de DA hacia pericardio, con fuga leve de contraste.

El paciente continua con dolor retroesternal quemante e hipotensión arterial.

Se inicia goteo de dopamina (400mg en 250 ml de SF a 10 microgotas por minuto), y reversión de heparina con 2 ampollas de protamina en infusión lenta.

Moderator’s Comments

First of all, I would like to congratulate the hemodynamics service at Hospital San Bernardo (Salta, Argentina) and, specially, Dr. Perez Solivellas for presenting the second case of The Fellow’s Corner.

The images are truly impressive, and I do not think anyone would have liked to be in the interventionist’s shoes at that moment.

We are dealing with a prior acute myocardial infarction, with a severe lesion in the middle third, which is complicated by a balloon retained during pre-dilation, and hemodynamic instability of the patient.

The physician decided to try to burst the balloon at high pressure and what happened next was a catastrophe, which may shorten the patient’s life. If faced with this scenario, how would you solve it?

This could happen to anybody, so I believe there is plenty to learn from this case. I encourage all fellows to participate in this discussion and share their experiences.

Here are my questions to spark the debate:

- When facing a stuck balloon, what are the available options to solve the situation?

- Do you agree with the course followed?

- When facing the end result, how do we solve it?

Again, I congratulate the presenter and thank him for sharing with us this challenging case that can happen to anyone in daily practice. It is paramount to always be prepared to solve these situations.

Remember: we will learn the final outcome of this intriguing case next week.

Greetings to all, have a nice week!

Dr. Nicolas Zaderenko.

We change the catheter for AL1 6F. We then proceed to insert 3 bare stents (REBEL: 2.5×16, 3.0×16, 3.0x16mm to 11 atm) overlapping from distal third to mid third, covering the stenotic lesion and perforation.

We perform bedside transthoracic echocardiogram that shows mild to moderate pericardial effusion with no collapse of right cavities.

We perform hemostasis at rupture site of DA with balloon 3.0x16mm to 8 atm in 6 opportunities, 2 minutes each.

Control angiography: patent DA, residual stenosis 0%, with no contrast leak.

We observe adequate result. We retrieve the inductor.

Control at ICU after 24 hrs.

Hemodynamically stable patient with no inotropic drugs, KK1, with no pericardial rub, tolerates decubitus.

ECG: T+/- precordial, lack of R progression.

ICU at 48hrs:

Spontaneous AF with RVR: patient is given digoxin and reverts to sinus rhythm.

ICU at 72hrs:

Echocardiogram:

VI: conserved diameters and thickness, left atrial mild dilation. Moderate extended hypokinesia in anterior and septal anterior walls. 49% EF with mild systolic dysfunction.

Diastolic G2 dysfunction, left ventricle with pseudo-normal filling pattern. E/a 18 (average). RVSP 43mmHg. Right cavities with conserved dimensions and functions. Valves S/P.

Mild posterior pericardial effusion.

We focused on 2 points of interest:

1. Failure to deflate:

a. CAUSE: failure to deflate a coronary balloon is extremely rare when using new material. This might happen when using reprocessed and resterilized material. Therefore, it is essential to check correct inflation/deflation before introducing second-hand balloons. The presence of a foreign body in the inflation hypotube, such as a remaining contrast crystal, could have been the cause. The “valve effect” created by such material would allow balloon inflation, but not deflation. Another mechanism could have been a twisted hypotube, even though this is more common in Inoue like balloons, in mitral valvuloplasty.

b. SOLUTION: How can we act to achieve balloon deflation without further iatrogenic injury? Insufflation pressure superior to that of balloon rupture should be the first choice. This was done in this case, but without causing the balloon to burst, but rather causing overdilation distal to the tube connecting with the balloon and its resulting explosion. This generated coronary rupture.

2. “Coronary rupture”:

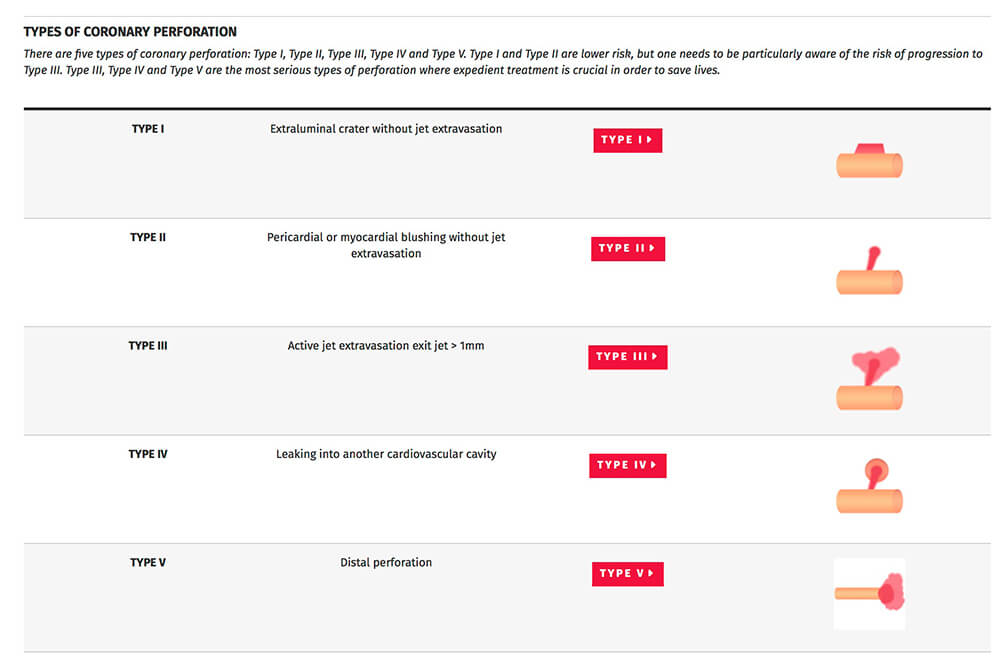

a. When treating a coronary rupture the first thing should be to define the type of rupture we are facing. Correct effusion classification will help us make the best choice, always on a case by case basis. The current classification, which extended to 5 categories the original S. Ellis classification, offers a comprehensive view for the diagnosis and management of this complication.

b. In this case, we have a type 3 rupture, since there is free extravasation of contrast into the pericardium. Even though the available dynamic image does not show this neatly enough, we can appreciate the left ventricle silhouette is separated from the pericardial contour, and a dark area of pericardial fluid because of the contrast dilution.

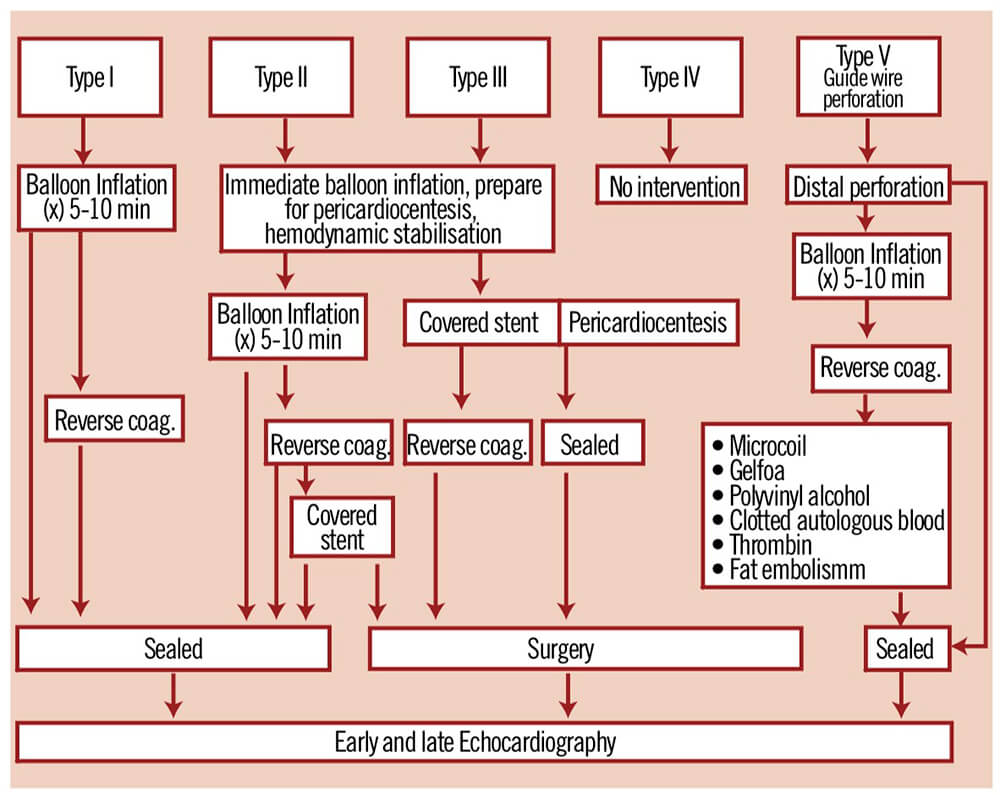

c. The rupture management algorithm shows a type 3 rupture requires the following measures:

- i. Neutralizing heparin

-

- ii. Insufflating an occlusion balloon at low pressure in the rupture area

- iii. Immediate access to echocardiogram

- iv. Alerting cardiac surgery

-

- v. Hemodynamics monitoring and stabilizing

- vi. Preparing maneuvers for eventual pericardial drainage

- vii. Checking availability of coated stent according to anatomy; be ready to use it in case of failure of the above stated

- viii. In case of failure to control the rupture within a sensible timeframe with the available resources, resort to emergency surgery procedure.

In this case, the complication was successfully solved with bare stent implantation (3) to lesion/rupture site and keeping vessel patency.

FINAL MESSAGE:

As a major takeaway, this case makes us reflect upon 2 aspects:

- When using reprocessed and resterilized material, quality control processes should be exhaustive and extreme at the precise time of use.

- In a modern cath lab, coated stents must always be available, since they will allow us to treat severe complications simply and effectively.

Congratulations to Dr. Pablo Solivellas for sharing this interesting case, to Drs. Lazarte, Rippa, Caprotta, Miara and Lopez Marinaro for their comments and to Dr. Nicolás Zaderenko for his initiative to support this exchange initiative at SOLACI.

Dr. Jorge Mayol

Ex Director of SOLACI SESSIONS

Co-Director of the Hemodynamics Service at the American Cardiology Center of the American Hospital in Montevideo, Uruguay

All you need to know about the Fellow's Corner

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

Get the latest scientific articles on interventional cardiology